5. Strategic autonomy

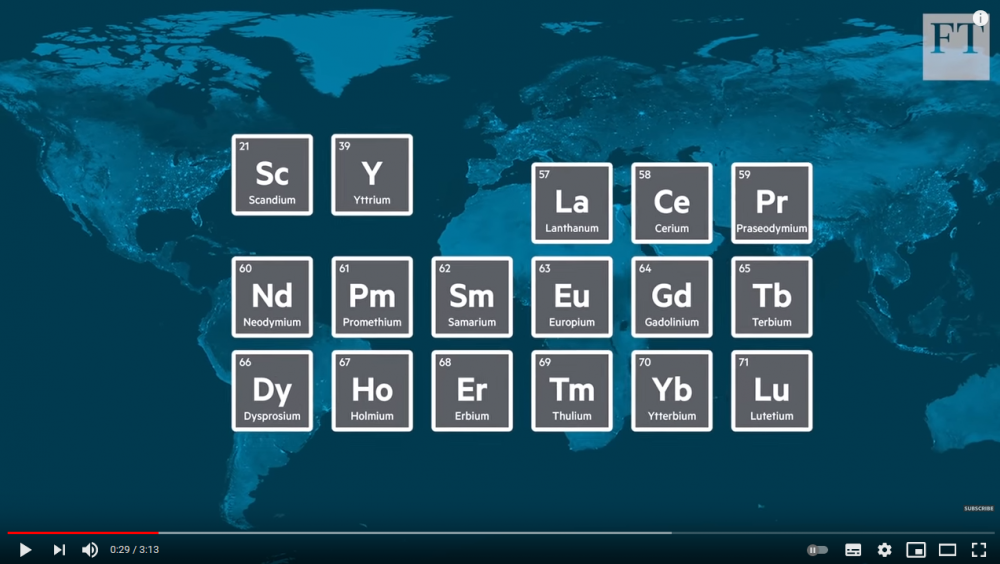

The EU is not dependent on China for rare earths alone. It is Europe’s main supplier for 10 out of 30 critical raw materials. (1) The EU is also heavily reliant on China for products containing these materials, such as solar cells, permanent magnets, batteries, and digital components and devices. This gives China leverage over the EU, not only on its energy and digital transitions but also its broader policies.

China’s quest for economic dominance is intertwined with its political aspiration to become a leading global power. The nature of the Chinese regime – autocratic with tech-totalitarian and imperial leanings – makes it a systemic rival to the EU. (2) A Europe that wants to protect and promote democracy, human rights, the rule of law, and multilateralism should not allow its path towards strategic autonomy to be undermined by Beijing's 'divide and conquer' politics.

Chinese infrastructure investments in countries such as Hungary and Greece have already provided Beijing with a foothold within the EU, enabling it to block European condemnation of its human rights violations. (3) The purchase of Chinese digital equipment for 5G networks, which comes with the risk of commercial and political espionage, has also divided the EU. In the energy sector, Europe’s dependence on China creates a political headache now that Chinese manufacturers of polysilicon metal for solar cells are heavily suspected of using forced labourers from the oppressed Uighur minority. (4) Spurred on by the European Parliament, the European Commission has announced a proposal to ban products made with forced labour. (5) Since the EU buys most of its solar cells and panels from China, such an import ban might well slow down Europe’s energy transition. While it is essential for the EU and China to cooperate in the fight against climate change, the EU must avoid trade-offs between climate protection and human rights.