Therefore, EU enlargement must be accompanied by an extension of qualified majority voting and a more robust oversight of democracy, human rights, and the rule of law within the EU’s borders. This is not excessive meddling in domestic affairs, because subversion of European values in a single country affects us all. The rules we live by partly come about through supranational decision-making in which each member state has a stake. The EU’s standing as a global actor depends not only on its diplomatic, economic, and military strength, but also on its adherence to its own values. Finally, EU security is at stake when, as in Hungary under Viktor Orbán, the backsliding of democracy goes hand in hand with pandering to Moscow and Beijing.

The EU should be an ally to citizens fighting back against democratic decline. In the case of Hungary, the evidence of serious breaches of the rule of law, democracy, and human rights is so overwhelming that the Article 7 procedure against Hungary must be taken forward urgently, leading to the suspension of the Orbán government’s voting rights in the EU Council. The EU institutions need to make much better use of their existing tools to protect European values.

For all that, the EU can only do so much on its own. Constitutional democracy requires constant care at all levels, not least by political parties.[29] From the centre right to the left, they should not form alliances with far-right populists, mimic their scapegoating of migrants and other minorities, or let their attacks on the judiciary, the press, and science go unchallenged. Nobody benefits from courting, copying, and trivialising the far right except the far right, as the 2023 Dutch parliamentary elections demonstrated once again.

The battle against illiberal right-wing populism can be won. Creeping authoritarianism is not an irreversible trend. In 2023, opposition parties and voters in Poland proved that. After the opposition rallied around European values, Polish citizens voted out their bigoted and abusive government.

Partnering with the Global South

Would a post-growth EU that considerably reduces its environmental footprint with the express purpose of freeing up natural resources for the Global South find allies there? This is an appealing but unlikely scenario. In a multipolar world, the governments of developing countries are disinclined to ally themselves with a single great power. Instead, it pays to sit on the fence, to play the US, the EU, and China off against each other so as to secure as much trade, aid, and investment as possible. The best the EU can hope for is a series of strategic partnerships of a non-exclusive nature, which are nonetheless vital for greater security and legitimacy.

Establishing and deepening partnerships would be easier if the older EU members came to terms with their colonial pasts. It should come as no surprise that many governments and citizens in the Global South refuse to see the Russian invasion of Ukraine for what it is: an imperialist, colonialist attack by a regime that has no regard for international law or human suffering. They associate imperialism and colonialism with Western Europe and the US. There is a huge amount of historical pain and anger that has still not been sufficiently addressed. Doing so would require unequivocal apologies for slavery and colonialism by all EU countries involved, as well as a frank recognition that the crimes of the past carry forward into present-day injustices, whether economic or ecological. Such declarations should be backed up by significant EU contributions to poverty reduction, global public goods, tax justice, legal migration routes, international climate finance, and compensation for climate loss and damage.

The EU should also team up with democratic governments in the Global South to develop proposals for the better representation of the South within the UN Security Council, the International Monetary Fund, and the World Bank. Last but not least, double standards must be avoided. An EU that helps defend Ukrainian statehood should also stand up for a viable, democratic Palestinian state, alongside a secure state of Israel.

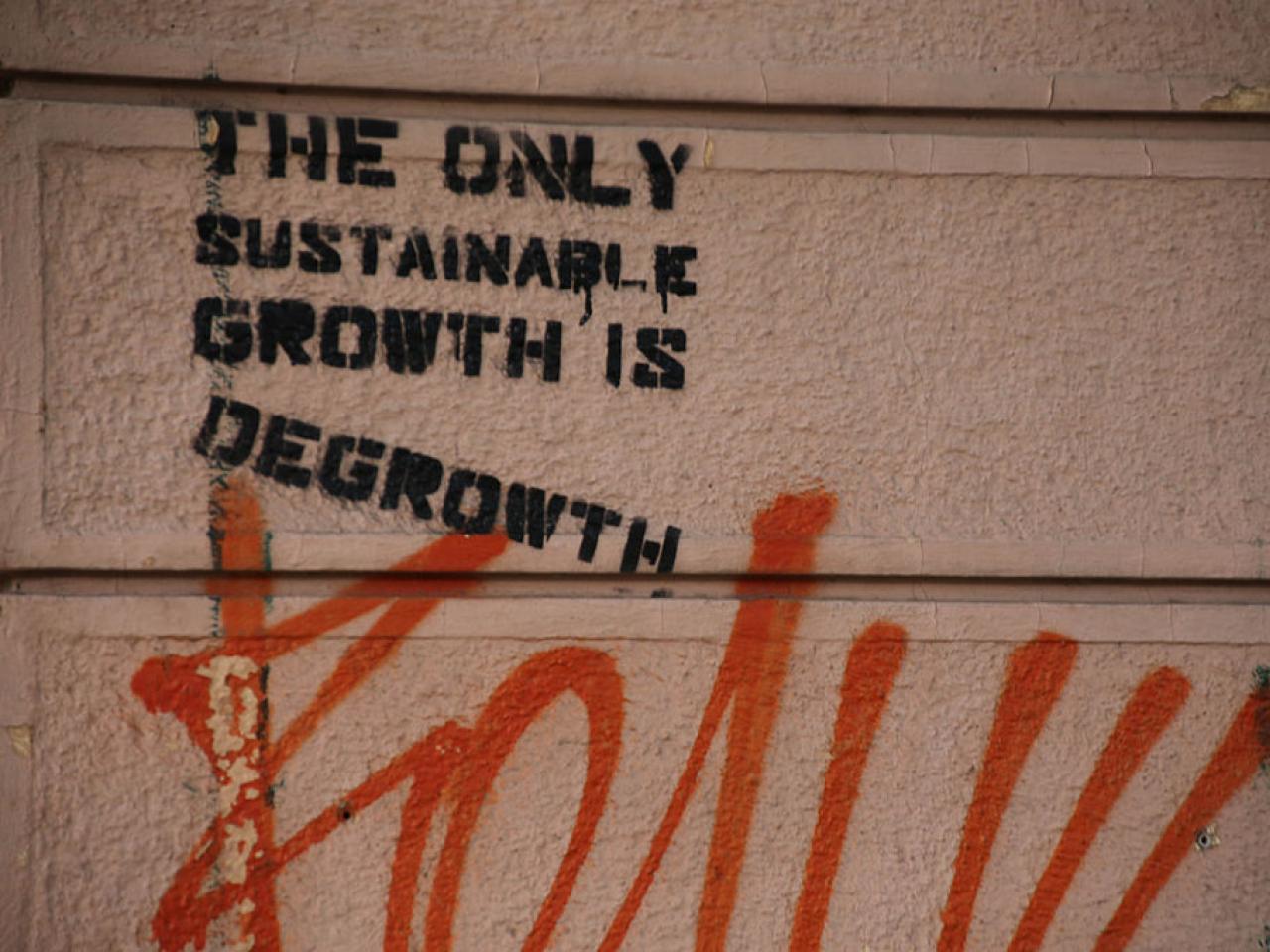

This part of the geopolitical agenda is a good fit with the degrowth movement’s aims of decolonisation and redistribution. It would benefit peace and democracy too, all the more so if interwoven with a feminist foreign policy that promotes the rights, representation, and resources of women and other disadvantaged groups. According to the World Bank, ‘Having more gender-equal societies results in more stable and peaceful states.’[30] All of this highlights that it would be unwise for a post-growth EU to cut costs on external action.

The biggest obstacle to partnerships between a post-growth EU and countries in the Global South might well be trade. In principle, many governments of developing countries would applaud firm action by the EU to reduce its overconsumption of global resources. In practice, however, such action could easily clash with their development strategies. Increasing the export of natural resources is often still viewed as a way to grow the economy, even by democratically elected, progressive governments of not-so-poor countries such as Brazil and Chile. Telling them that we know better might bring back memories of colonial times.

Action speaks louder than words. An EU that pushes through debt cancellation, for instance, would ease the pressure on developing countries to sell off chunks of their lithosphere and biosphere in order to pay back foreign creditors. This could open up the debate to alternative (de)growth strategies for the Global South, not focused on exports.[31] But still, it is up to the polities of the South to choose their own development paths. For now, these are not aligned with post-growth in Europe.